Category: Wildlife

Ospreys nesting at Alameda Point interrupted again in 2014

In early June a pair of returning ospreys looked ready for the day in their newly made nest atop a parking lot light pole at Alameda Point, but they had no chicks to attend to. The pair’s first nest this season — on a nearby ship — had been removed during construction. Their second attempt faced interference from another osprey. By June, hopes for fledglings this year had faded. An ad hoc group of osprey watchers is hoping a dedicated osprey platform can be erected at Alameda Point in a spot where competing interests and annoyances of daily commotion don’t intrude into the reproductive efforts of the ospreys.

In early March the osprey pair began building their first nest this year where they had nested last year — on a kingpost high atop the maritime ship Admiral Callaghan. The ship’s owner, the Maritime Administration (MARAD), had removed last year’s nest. This year MARAD moved quickly to stop the nest building to avoid potential delay to relocate a nest if ordered into service. “The Maritime Administration worked closely with the California Department of Fish and Wildlife on dismantling the nest and installing deterrence devices on March 19 prior to any eggs being laid,” said Alameda resident Harvey Wilson, who has been monitoring the ospreys at Alameda Point.

But that removal didn’t end the ospreys’ interest in the ship, at least not for the male osprey. He soon started bringing sticks to a lower-level hoisting post on the ship. The female, on the other hand, took a liking to a light pole in the parking lot next to the wharf. After weeks of back and forth episodes of mating and nest building at both sites, the female won, and nest building started ramping up on the light pole. At one point, it appeared that the female was hunkering down in the nest, a sign that eggs had been laid and incubation had started. But soon another female osprey appeared, trying to lure the male from his duties and disturbing the composure of the female.

The third osprey now seems to have moved on, and the original pair has continued to visit the nest, but the lateness of the season offers little hope that eggs will be laid again, if they ever were, this year.

The appearance of ospreys at Alameda Point, first documented in 2010, is part of larger Bay Area phenomenon of ospreys beginning to nest on the shores of San Francisco Bay. Osprey first began nesting in the San Francisco Bay Area in the year 2000, having moved their nesting range further south. There are currently 24 active nests on San Francisco Bay. One theory for the ospreys’ Bayside nesting interest is a reduction of silt in the Bay, making it easier for osprey to catch fish, their primary food source. The high silt levels are a legacy of the gold mining era during which streambeds emptying into the Sacramento River were blasted with water canons to expose gold particles. Ospreys normally return to the same nest every year, but the Alameda Point pair has now used three different sites. In 2012 they successfully raised their lone chick on an old light stand on the western jetty of the Seaplane Lagoon, their regular nest for three years. For unknown reasons, they chose the heights of a maritime ship in 2013, and in 2014 a parking lot light pole.

An ad hoc group of osprey watchers that includes members of the Golden Gate Audubon Society have been discussing with the city the possibility of erecting a permanent osprey nesting platform on the western side of the Seaplane Lagoon. “City staff has been and is willing to continue to work with interested members of the local community to potentially establish an osprey platform at Alameda Point,” said Jennifer Ott, Chief Operating Officer for Alameda Point. “The identification of an appropriate location for this platform will depend on a number of factors, including approval by the United States Fish and Wildlife Service.” In March of this year, the city of Richmond’s Public Works Department assisted with the installation of an osprey platform at Pt. Molate, which helped divert nesting efforts from a utility pole with live wires. PG&E, with extensive raptor nesting diversion experience throughout California, has offered to install a pole and nesting tub at Alameda Point for free.

“It is difficult to know what the ospreys feel or how they respond or what their capacity is for all the activity that goes on around them, but this season certainly challenged them,” said Alameda wildlife biologist Leora Feeney. “Providing safe platforms for them out of busy corridors would serve everyone better.”

Published on the Golden Gate Audubon Society’s blog Golden Gate Birder.

See also:

- “Ospreys’ nesting effort draws competition atop maritime ship” on Alameda Point Environmental Report.

- “Young osprey at Alameda Point leaving soon” on Alameda Point Environmental Report.

- “Ospreys take a liking to San Francisco Bay” in Bay Nature.

- “Pt. Molate — Where Osprey Come To Nest” on Citizens for a Sustainable Point Molate website.

- PG&E’s “Protecting Birds” page.

Shoreline grassland, wetland: An opportunity now at Alameda Point

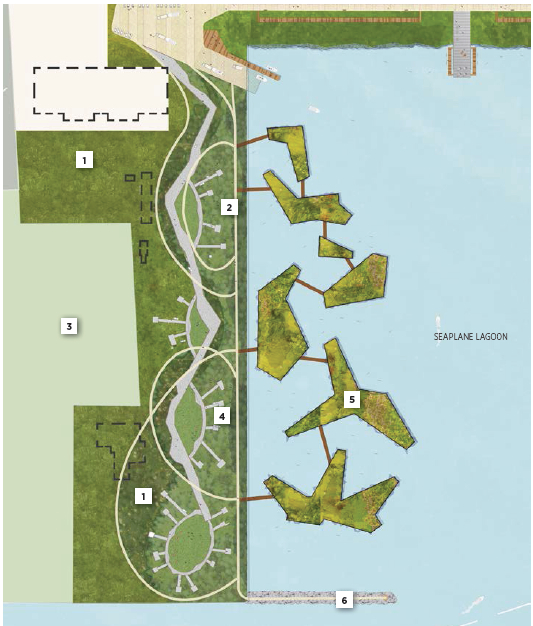

The city’s west side of the Seaplane Lagoon at Alameda Point is mostly pavement – acres of it – with a few old buildings abutting a wetland on the federal property. The city claims its long-range plan for this area features a conversion to a wetland habitat, but their only commitment is to continue leasing the buildings to generate revenue while allowing a sea of unnecessary pavement to remain as an environmental blight.

Opportunities for implementing ecosystem enhancement, both short and long term, have yet to be explored for this area. We need to start moving in a direction now that benefits the environment by reducing climate impacts, improves the atmosphere around nearby businesses, adds to public enjoyment, and increases wildlife habitat.

Proposal for ecosystem enhancement

Short-term plan – Remove all pavement not required for commercial tenants. Recycle the pavement at the VA’s Alameda Point project site where they will be raising elevation and need base rock and fill. Once the pavement is removed and the soil exposed, native vegetation could be planted. Native vegetation will absorb CO2, produce oxygen, eliminate the heat island effect of the former pavement, add wildlife habitat, improve the aesthetic appearance of the property, and make it attractive as a hiking, jogging, and cycling destination.

Step 1 – Set aside money from lease revenue generated on the west side of the Seaplane Lagoon for pavement removal and introduction of native plant vegetation.

Step 2 – Explore recycling pavement at Alameda Point.

Step 3 – Explore grant sources for conversion of paved areas to native vegetation, i.e., state air quality board, EPA, State Lands Commission, etc.

Long-term plan – Establish an Alameda Point Wetland Mitigation Bank, which would incorporate the west Seaplane Lagoon acreage along with 50 acres on the northwest side of Alameda Point (Northwest Territories). Investment money would provide the capital for wetland creation, with money being recouped when mitigation credits are sold to developers elsewhere in the Bay watershed to offset their project’s impacts. As a general rule, a tidal wetland is worth at least as much as it would cost to create it. That’s why businesses exist that specialize in mitigation banks. In theory at least, the wetland project could be self-funding.

Step 1 – Commission a study on wetland mitigation bank formation using lease revenue from Buildings 25 and 29.

Information about wetland mitigation banking:

Report To The Legislature – California Wetland Mitigation Banking – Jan. 2012

U.S. Wetland Banking – Market Features and Rules

Forbes wetland article 4/25/2014 from BCDC

Take the plunge! Remove pavement on the west side of the Seaplane Lagoon and improve our environment.

Black-crowned Night Heron Juvenile – Gallery and Video – Spring 2014

A Black-crowned Night Heron adult and its juvenile offspring were spotted along the south shoreline of Alameda Point during May and June of this year. The juvenile was seen foraging for food on the shoreline, as well as using the old dock for a resting area. Use of the old dock by a wide variety of birds, as well as a family of harbor seals, illustrates the habitat value of the waterfront and the wisdom of providing a new wildlife water platform when the Water Emergency Transit Authority removes the old dock for their new maintenance facility this year.

Bird Life at Alameda Point – Fall 2013

Featured here is a sampling of the wide variety of birds that enjoy the Alameda Point environment, from the wooded residential neighborhood and wooded parkland, to the shoreline, to the wide open runway area. Most notable of recent sightings is the Golden Eagle, which has been seen off and on for at least a year hunting for rabbits and other prey on the runway area Nature Reserve.

Brown pelicans of Alameda’s Breakwater Island – September 2013

Breakwater Island runs along the south side of the Alameda Point Channel. It was officially transferred from the Navy to the City of Alameda in June of 2013. It is the largest night roosting site for California brown pelicans in San Francisco Bay. During the warm months, hundreds of pelicans can be seen on the breakwater. An early September kayak trip past Breakwater Island found their numbers down to a few dozen, most likely due to good fishing elsewhere in the Bay Area. By December most of the pelicans will have migrated south to places such as the Channel Islands where they nest.

Hawks on the Nature Reserve at Alameda Point

Red-tailed Hawks are regular visitors to the Nature Reserve on the former airfield at Alameda Point. The Northern Harrier, another type of hawk, also visits the reserve, but are fewer in number and harder to spot.

Red tails and harriers both like the wide open space and grassland where they hunt for prey, but they differ in their abilities to hunt. The red tails rely on keen vision and are able to hunt from great heights and distance. Harriers, on the other hand, rely on hearing in the same way that an owl does. The harrier’s face has characteristics similar to an owl that allows it to capture sounds and direct them to their ears. They have the ability to hear the sounds of small animals moving in the grass. They fly close to ground, sometimes within 10 feet, methodically moving about listening for movement.

Occasionally during the least tern nesting season red tails and harriers prey on the terns and have been trapped by the Fish & Wildlife Service and relocated further inland. Red tails can catch jackrabbits, but harriers might have a tough time with a full-grown rabbit and look instead for small rodents.

Adding more grassland on the periphery of the Nature Reserve would help the least terns by providing more hunting opportunities for predators away from the nesting site. These wild and magnificent birds are but two examples of why the Nature Reserve offers unique opportunities for wildlife habitat enhancement.

The two birds below were photographed in September of 2013.