The endangered least terns have returned. Committed volunteers prepare and maintain this unique site during the non-nesting season. The public can see the fruits of their work on June 15.

2013 maintenance work began on January 13th by clearing weeds from the outer perimeter of the nesting area. The terns need a clear view of their surroundings to feel comfortable that predators are not lurking nearby. Trimming vegetation near the nesting area is a high priority on work party checklists.

Volunteers were at the site again in February, March, and early April prior to the terns’ mid-April arrival. Tasks included replacing deteriorated plastic mesh along the base of the fence around the nesting site. The plastic mesh keeps chicks from wandering out through openings in the chain link fence. The chain link fence is there to keep out predators, and to keep out rabbits that might easily trample eggs.

Another of set of tasks involves randomly placing wooden A-frames and half-round clay tiles that serve as shelters for the chicks from predators like hawks. One of the senior volunteers has been working to help the terns since the base closed. This year he brought 48 wooden chick shelters that he made at his home. Another task is the distribution of oyster shells that make it harder for flying predators to distinguish where the chicks are located.

The number of volunteers ranged from 12 to as many as 30 each month. Among the volunteers this season were members of the Tau Beta Pi engineering fraternity at UC Berkeley, which has been sending volunteers for many years, and members of the Encinal High School Key Club.

Volunteers will return in September after the terns are gone. They will gather up the A-frames, clay tiles, oyster shells, and the numbered plaster markers that the US Fish & Wildlife Service uses to keep track of nesting success. Picking up the “tern furniture” allows for weed control and periodic grading of the sand and gravel.

During May, June, and July, another set of volunteers participate in the “Tern Watch Program.” Volunteers are trained in recording observations as they watch from their vehicle near the nesting site. A cinder block grid system helps in recording feeding activity, among other things. If predators are threatening the colony, the volunteers alert the Fish & Wildlife Service in the office nearby.

Volunteer opportunities:

- Tern Watch Program

- Work parties, organized by Golden Gate Audubon Society: Contact Joyce Larrick at jmlarrick@yahoo.com Next work party is the second Sunday in September.

Return of the Terns tours

On June 15th, the general public gets an opportunity to observe the nesting activity of the terns during a bus tour to the site. The tours leave from Crab Cove Visitor Center in Alameda. Registration and a fee are required. More info is on the Return of the Terns flyer.

Previous stories about the least terns:

Least terns depart – volunteers move in at Alameda Point refuge

Protecting the California Least Terns at the Alameda Point Wildlife Refuge

January – April 2013 Photo Gallery

Click on photos to enlarge and view slideshow

“This is not just about counting birds,” said Gary Langham, Audubon’s chief scientist. “Data from the Audubon Christmas Bird Count are at the heart of hundreds of peer-reviewed scientific studies and inform decisions by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the Department of the Interior, and the EPA. Because birds are early indicators of environmental threats to habitats we share, this is a vital survey of North America and, increasingly, the Western Hemisphere.”

“This is not just about counting birds,” said Gary Langham, Audubon’s chief scientist. “Data from the Audubon Christmas Bird Count are at the heart of hundreds of peer-reviewed scientific studies and inform decisions by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the Department of the Interior, and the EPA. Because birds are early indicators of environmental threats to habitats we share, this is a vital survey of North America and, increasingly, the Western Hemisphere.” John’s 50 years of observing birds in every California county is evident in his quick identifications and economy of movement with his spotting scope. “There’s a Common Loon…and…it just went under…there it is…turn around(as if speaking to the bird)…it’s… a Red-throated Loon,” he would say. “White-crowned Sparrows – two.”

John’s 50 years of observing birds in every California county is evident in his quick identifications and economy of movement with his spotting scope. “There’s a Common Loon…and…it just went under…there it is…turn around(as if speaking to the bird)…it’s… a Red-throated Loon,” he would say. “White-crowned Sparrows – two.” The biggest surprise came at the thick stand of willows at the north boundary of the refuge. There, just inside the branches was a Great Horned Owl, a bird that Leora said she had never seen in eight years of doing twice-monthly bird surveys on the refuge. Even more surprising was how approachable the owl was as it was being photographed, slowly turning its its head 180 degrees, appearing fearless.

The biggest surprise came at the thick stand of willows at the north boundary of the refuge. There, just inside the branches was a Great Horned Owl, a bird that Leora said she had never seen in eight years of doing twice-monthly bird surveys on the refuge. Even more surprising was how approachable the owl was as it was being photographed, slowly turning its its head 180 degrees, appearing fearless.

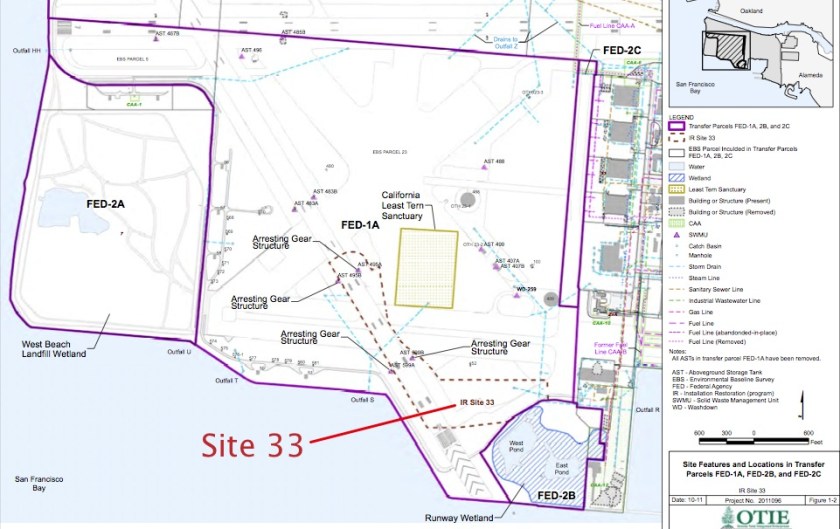

The study went on to extol the intersecting virtues of wildlife habitat protection and economic value. “While important in their own right, the benefits that would be generated by establishment of the wildlife refuge are not limited to habitat and species protection,” stated Hrubes and Associates. “[T]here are indeed potential economic benefits that could derive from a wildlife refuge/day-use recreation area located in the central Bay Area. That is, the wildlife refuge proposal is not an ‘either/or’ choice between environmental quality and economic development. Rather, it constitutes a land use that not only will take optimal advantage of the environmental attributes the site has to offer but also will generate economic activity that benefits the local region. Further, it will enhance the economic value for development of the remainder of the NAS.”

The study went on to extol the intersecting virtues of wildlife habitat protection and economic value. “While important in their own right, the benefits that would be generated by establishment of the wildlife refuge are not limited to habitat and species protection,” stated Hrubes and Associates. “[T]here are indeed potential economic benefits that could derive from a wildlife refuge/day-use recreation area located in the central Bay Area. That is, the wildlife refuge proposal is not an ‘either/or’ choice between environmental quality and economic development. Rather, it constitutes a land use that not only will take optimal advantage of the environmental attributes the site has to offer but also will generate economic activity that benefits the local region. Further, it will enhance the economic value for development of the remainder of the NAS.”

However, based on public statements from the VA about their timeline for construction, it does not appear that they have any intention of doing a full EIS, and thus their environmental commitment will be limited. This will mean that rather than adding grasslands to perimeter areas that already have pockets of grasslands between runways and taxiways in order to divert hawks and other avian predators away from nesting terns, they will keep the refuge looking as much like a fenced-in stadium parking lot as possible (like it has been for the past decade). The pretext is that it removes habitat for predators, but in this case they would be torturing the concept by making the tern nesting site so conspicuous that it will invite predation. Virtually all of the least tern predation events have been from flying predators—like the peregrine falcons that come from miles away on the other side of Alameda.

However, based on public statements from the VA about their timeline for construction, it does not appear that they have any intention of doing a full EIS, and thus their environmental commitment will be limited. This will mean that rather than adding grasslands to perimeter areas that already have pockets of grasslands between runways and taxiways in order to divert hawks and other avian predators away from nesting terns, they will keep the refuge looking as much like a fenced-in stadium parking lot as possible (like it has been for the past decade). The pretext is that it removes habitat for predators, but in this case they would be torturing the concept by making the tern nesting site so conspicuous that it will invite predation. Virtually all of the least tern predation events have been from flying predators—like the peregrine falcons that come from miles away on the other side of Alameda. The real reasons for maintaining the industrial look are to reduce maintenance and capital costs, and to exploit the paved areas for

The real reasons for maintaining the industrial look are to reduce maintenance and capital costs, and to exploit the paved areas for