There are faster ways to clean up industrial solvents in groundwater, but the only viable choice for a large contamination site at Alameda Point was to turn the job over to bacteria. Known as bioremediation, a unique bacteria is breaking apart the solvent trichloroethene (TCE), also known as trichloroethylene, into a harmless substance.

It takes time and the right conditions for the bacteria to thrive—namely, an absence of oxygen and the presence of a carbon source. Readily-available carbon sources to pump into the contamination area just happen to be soy vegetable oil and dairy lactose.

The contamination area lies immediately south of the jet monument on West Atlantic Avenue and extends from Building 360, currently used by rocket company Astra, to the street in front of the Seaplane Lagoon ferry terminal. The remediation plan aims to see that the toxic solvent never reaches the lagoon. Some 19 acres were contaminated by solvent used by the Navy for degreasing engine parts as they were being refurbished, much of it emanating from Building 360.

If not for all of the underground utility infrastructure in the area, some of which were not recorded on Navy maps, the Navy could have used faster cleaning methods, such as injecting a neutralizing chemical to break down the solvent. But the presence of sewer, water, gas, and electric pipes meant that when the cleanup chemical hit the pipes much of it would then travel along the pipes, rather than evenly disperse throughout the contamination zone, thereby defeating the purpose. A thriving bacteria, on the other hand, becomes a self-replicating, self-expanding cleanup machine—up, down, and sideways—regardless of pipes.

Bioremediation began in 2017

The Navy began its bioremediation work on this contamination site in 2017. The first round of injections was lactose, a form of sugar found in milk. “It’s going to bolster the population of a lot of the organisms that are present,” said Dr. David Cacciatore with Navy contractor CB&I Federal Services, Inc., speaking to a meeting of the Restoration Advisory Board in March 2017. Subsequent rounds of injections utilized a special blend of emulsified soybean oil, lactose, baking soda as a pH buffer to reduce acidic conditions, and an additive with vitamin B12 to reduce dissolved oxygen in the fire hydrant water being used to mix the solution onsite.

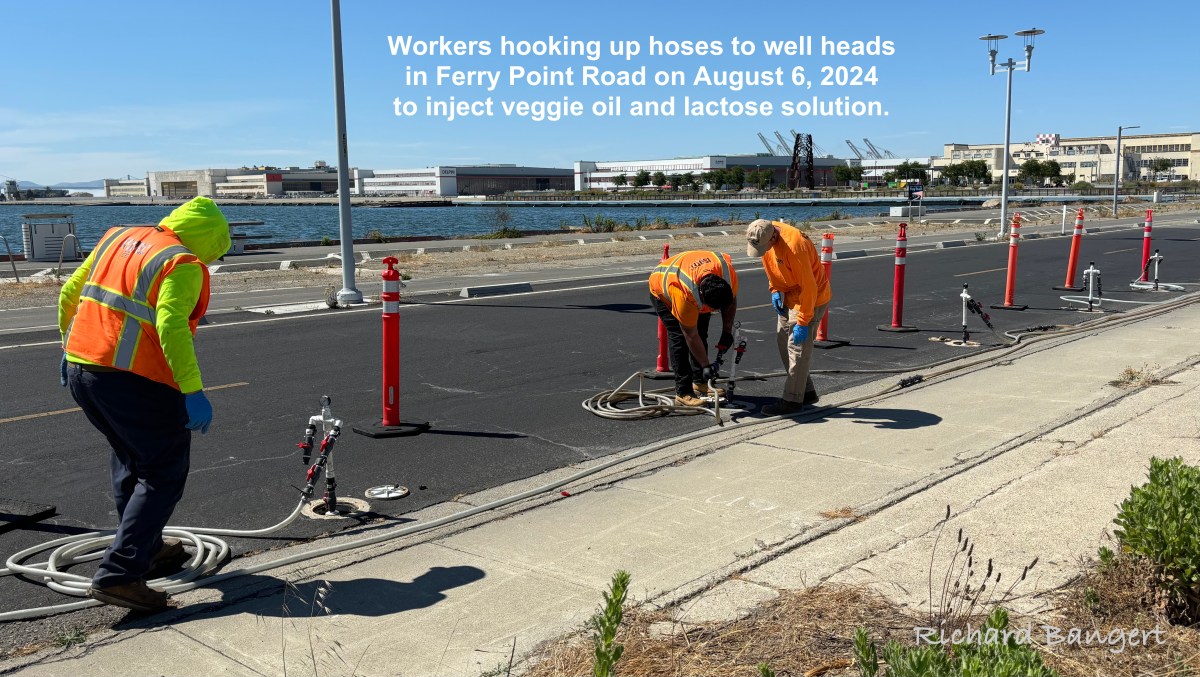

The near term goal is to reduce the amount of TCE to point where commercial enterprises can conduct business without risk of harmful vapors. The Navy almost reached its goal after the fourth round of injections in 2021, but regulators wanted to see more signs of progress. That’s why a new contractor was onsite for the month of July and into August for the fifth round of injections of some 229,000 gallons of treatment mixture into 348 wells.

Until the near term remedial goals are met, the land will not be authorized for transfer from the Navy to the city. And until the city gets the land, the Site A developer Alameda Point Partners cannot complete their development plan. Nor can the city sell other land in the cleanup area.

Most of Alameda Point has already been cleaned up, at a cost of over $500 million, and transferred by the Navy.

How it works

TCE is a chlorinated hydrocarbon composed of chlorine, hydrogen, and carbon. Chlorine is particularly toxic. Fortunately, scientists have found a naturally-occurring bacteria called dehalococcoides that likes chlorine. Under the right conditions, the bacteria strips off chlorine atoms, not all at once, but one by one. The “tri” in trichloroethene goes to dichloroethane, still highly toxic. When another chlorine atom is stripped off, it turns into vinyl chloride, still toxic. The final step in the process reduces this formerly toxic solvent to a harmless gas called ethene.

Ethene, or ethane, is a gas that breaks down naturally to carbon dioxide and water. It is also known by the name ethylene, and is the same chemical that is used to ripen fruit.

The proper analogy for the process, in human terms, would be eating and breathing. The bacteria are eating the lactose and/or emulsified vegetable oil substrate and breathing the TCE. Bacteria utilize the food source as an electron donor in the energy generation process, and in a parallel process utilize an electron acceptor in TCE for respiration.

Basically, the bacteria are switching electrons between the veggie oil/lactose and the TCE. “TCE acts as an electron acceptor, while chlorine is simultaneously removed from TCE,” states this 2022 report on TCE bioremediation from the U.S. National Center for Biotechnology Information. The veggie oil and lactose are the donors. This movement of electrons also creates a certain amount of energy that can be used for microbial growth, according to the report.

Availability and cost are the reason why vegetable oil and lactose are used. In 2024, 86 million acres of soybeans were planted in the U.S. And dairy farms are everywhere.

Necessary conditions for remediation

The bacteria that likes chlorinated solvent requires an oxygen free (anaerobic) environment to live. Oxygen is toxic to this bacteria. This is why an additive is included in the veggie oil solution to eliminate, or scavenge up, dissolved oxygen in water.

Water is composed of hydrogen and oxygen. But in addition, there is also oxygen that is just floating around in the water called dissolved oxygen. Aquatic organisms utilize dissolved oxygen for respiration. It is necessary for the survival of fish, invertebrates, bacteria and underwater plants. However, dissolved oxygen is toxic to strictly anaerobic bacteria like dehalococcoides, which is responsible for complete dechlorination of TCE to ethene.

How do regulators know if the groundwater cleanup is working?

Periodic groundwater testing looks for the presence of TCE and the chemicals it is being broken down into and whether the rate of breakdown is on track.

Below, workers are monitoring pressure in the hoses produced by generator in the background. Pressure needs to remain around 20 pounds, or else the solution may start to back up and out of the wells because the groundwater and soil cannot absorb it fast enough.

Originally published on the Alameda Post.

Richard – I found this report fascinating. Thank you for explaining this process.

LikeLike